We need to change the conversation on investment management fees. The debate on fees needs to be based on facts rather than myths. Despite often being framed in this way, the debate on investment management fees is not black versus white.

What matters is not the fee level, but the manager’s ability to deliver a satisfactory outcome to investors after fees. Either way, it is no good paying high fees or the lowest possible fees if your investment objectives have not been achieved. Therefore, amongst the key questions to ask are, are you satisfied with the investment outcomes after the fees you have paid? – have your investment objectives or retirement goals been achieved?

After fee returns are important. Therefore, higher fee investment strategies should not necessarily be avoided if they can assist in meeting your investment objectives. In the current investment environment, the use of higher fee investment strategies may be necessary to achieve your investment objectives.

Therefore, Investors should focus on given the investment outcomes have I minimised the fees paid.

In my mind, this would be consistent with the FMA’s value for money focus. (FMA is New Zealand’s Regulatory)

At the same time, fees should not be the overriding concern and investors must analyse fees in the overall context of managing their portfolios appropriately.

Investment management fee Myths

The 5 most common myths about investment management fees are:

- Fees should be as low as possible

- Incentive fees are always better than fixed fees

- High water marks always help investors

- Hedge Funds are where the alpha is. They deserve their high fees

- You can always separate alpha from beta, and pay appropriate fees for each

This paper, Five Myths About Fees, address the above myths in detail.

Although all the myths are important, the myth that fees should be as low as possible probably resonates most with investors.

Investment management fees for active management are higher than index management and involve a wealth transfer from the investor to the investment manager. This is a fact.

However, the paper is clear, investors should look to maximise excess returns (they term alpha) after fees. Another way of looking at this, for a given level of excess returns, fees should be minimised. This is an important concept when considering the discussion below around broadening the discussion on fees.

The paper also notes, investors should pay higher fees to those managers that are more consistent. For example, if two managers provide the same level of excess return, but one does so by taking less risk, investors should pay higher fees to this manager (the manager who achieves the same excess return but with lower risk – technically speaking, this is the manager with the higher information ratio).

In summary, the take-outs on the myth fees should be as low as possible:

- Fees must remain below expected excess returns e.g., a manager that charges active fees but only delivers enhanced index returns should be avoided.

- Managers who consistently add value warrant higher fees.

In relation to do managers add value, see this Post, Challenging the Conventional Wisdom of Active Management.

The paper on the five fee myths is wide ranging. It also provides insights into the key elements of the fee negotiation game and determining the conditions under which higher fees should be paid.

Key conclusions from the article, particularly after addressing Myth 4 & 5:

- most investment strategies offer a combination of cheaply accessible market index returns (beta) and active management excess returns (alpha). While many institutional investors look to separate beta and alpha for most investors this is too limiting and difficult. Many talented investment managers appear in investment strategies which include both beta and excess returns (alpha).

- Investors should consider fees before deciding on an investment strategy, not look at an investment strategy and then consider fees.

- At the same time, fees should not be the overriding concern.

- High fee investment strategies are worthwhile if they deliver sufficient return and lower risk.

- Investors must analyse fees in the overall context of managing their portfolios appropriately.

A framework for Changing the discussion on fees

Despite it often framed this way, the debate on fees is not black versus white.

From this respective, understanding the disaggregation of investment returns can help in broaden the debate on fees and also help determine the appropriateness of fees being paid.

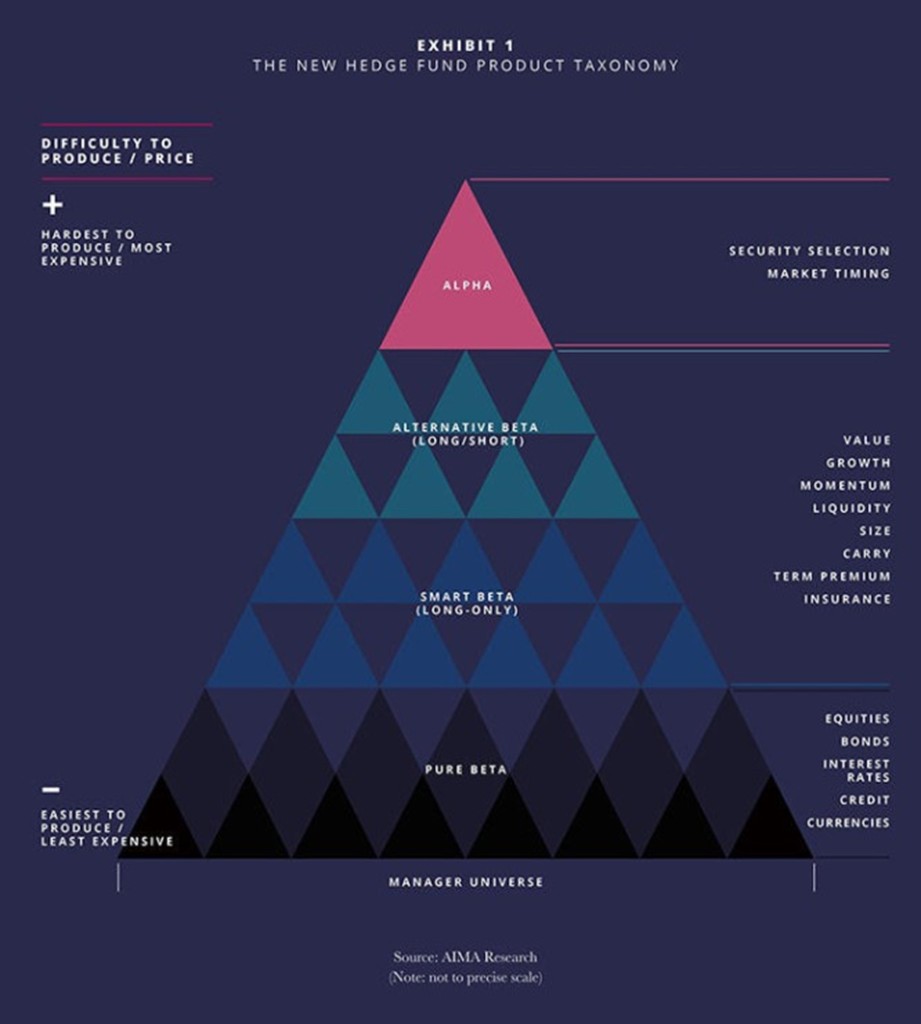

From a broad view, investment returns can be disaggregated in to the following three parts:

- Market beta. Think equity market exposures to the NZX50 or S&P 500 indices (New Zealand and America equity market exposures respectively). Market Index funds provide market beta returns i.e. they track the returns of the market e.g. S&P 500 and NZX50. Beta is cheap, as low as 0.01% for large institutional investors.

- Factor betas and Alternative hedge fund beta exposures. Of the sources of investment returns these are a little more ambiguous and contentious than the others. This mainly arises from use of terminology and the number of investable factors that are rewarding. My take is as follows, Factor betas and Alternative hedge fund beta fit between market betas (above) and alpha (explained below).

- Factor Beta exposures. These are the factor exposures for which I think there are a limited number. The common factors include value, momentum, low volatility, size, quality/profitability, carry. They are often referred to as Smart beta.

- Alternative hedge fund betas. Many hedge fund returns are sourced from well understood investment strategies. Therefore, a large proportion of hedge fund returns can be explained by common hedge fund risk exposures, also known as hedge fund beta or alternative risk premia or risk premia. Systematic, or rule based, investment strategies can be developed to capture a large portion of hedge fund returns that can be attributed to a hedge fund strategy (risk premia) e.g. long/short equity, managed futures, global macro, and arbitrage hedge fund strategies. The alternative hedge fund betas do not capture the full hedge fund returns as a portion can be attributed to manager skill, which is not beta and more easily accessible, it is alpha.

- Alpha is what is left after all the betas. It is manager skill. Alpha is a risk adjusted measure. In this regard, a manager outperforming an index is not necessarily generating alpha. The manager may have taken more risk than the index to generate the excess returns and/or they may have an exposure to one of the factor betas or hedge fund betas which could have been captured more cheaply to generate the excess return. In short, what is often claimed as alpha is often explained by a factor or alternative hedge fund beta outlined above. Albeit, there are some managers than can deliver true alpha. Nevertheless, it is rare.

These broad sources of return are captured in the diagram below, provided in a hedge fund industry study produced by the AIMA (Alternative Investment Management Association).

The disaggregation of return framework is useful for a couple of important investment considerations. We can use this framework to determine:

- Appropriateness of the fees paid. Obviously for market beta low fees are paid e.g. index fund fees. Fees increase for the factor betas and then again for the alternative hedge fund betas. Lastly, higher fees are paid to obtain alpha, which is the hardest to produce.

- If a manager is adding value – this was touched on above. Can a manager’s outperformance, “alpha”, be explained by “beta” exposures, or is it truly unique and can be put down to manager skill.

The consideration of this framework is consistent with the observations from the article above covering the 5 myths of Investment Management Fees.

Lastly, personally I think a well-diversified portfolio would include an exposure to all of the return sources outlined above, at the very least.

Many institutional investors understand that true portfolio diversification does not come from investing in many different asset classes but comes from investing in different risk factors. See More Asset Classes Does not Equal More Diversification.

From this perspective, the objective is to implement a portfolio with exposures to a broad set of different return and risk outcomes.

Please read my Disclosure Statement

For Outsourced Chief Investment Officer (OCIO) and investment consulting services please see here.

Global Investment Ideas from New Zealand. Building more Robust Investment Portfolios.