To all Kiwi Investor Blog readers, I hope you are staying safe and healthy. My thoughts are with you from a health perspective and for those facing the economic consequences on businesses and families from the spread of the coronavirus.

In the current market environment there is much uncertainty and many are wondering what to do with their investments.

The key questions being asked are should we switch to a more conservative investment or get out the markets all together.

One of the best discussions on why to remain invested is provided by FutureSafe in a letter to their client’s 15th March.

FutureSafe provide one reason why it might be the right thing for someone to reduce their sharemarket exposure and three reasons why they might not.

They have reproduced the letter in the hope that it might be helpful and of interest to the broader investing community.

As they emphasis, please consult your advisor or an investment professional before making any investment decisions. In New Zealand, the FMA has also provided recent guidance on this issue, KiwiSaver providers should be providing general (class) advice to members at this time. Their full guidance on Kiwisaver Advice is here.

I have provided the main points below of the FutureSafe letter to clients, nevertheless the letter is well worth reading in full.

The first question is do you have too much invested in the market?

As FutureSafe highlight, the average declines of bear markets since WWII have been over 30%, with some declines as large as 60%. It has generally taken on average 2 years to recover.

My last Post, What to expect, navigating the current Bear-Market, presented research from Goldman Sachs on the historical analysis of bear markets in US equities going back to the 1800s. At this stage, we are likely experiencing an Event-Driven Bear market. These Bear markets tend to be less severe, but the speed of the fall in markets is quicker, as is the recover.

However, as Goldman Sachs note none of the previous Event-Driven Bear markets were triggered by the outbreak of a virus, nor were interest rates so low at the start of the market decline.

Historically Event-Driven bear markets on average see falls of 29%, last 9 months and recover within 15 months. Nevertheless, the current Bear could transform into a cyclical bear market if containment efforts lead to a larger global recession than anticipated.

Back to FutureSafe. You should only take the risk you can stomach, or technically speaking, is aligned with your “risk appetite”. Which is a level of risk that does not keep you awake at night. Unfortunately, we often don’t know our risk appetite until we experience significant market events like we are experiencing currently. We are often over-confident as to the level of market volatility we can tolerate.

FurtureSafe conclude “Now that we are in a downturn, if you have come to the conclusion that your risk appetite is not what you thought it was, it’s perfectly OK to acknowledge that and change your safety net accordingly.”

However, before you do anything, FutureSafe ask you to read through and consider a few reasons why not to do anything at this time might be appropriate.

Reason 1

If management of risk appetite is not your motivation, perhaps you are planning on selling now, with the conviction markets will continue to fall, and you plan on buying back in later.

You are essentially making an active investment decision and attempting to time markets.

Timing markets is very hard to do. Professional Investors are not very good at it.

The data on the average mutual fund investor is also not very complimentary. As FutureSafe note the “the average mutual fund investor has not stayed invested for a long enough period of time to reap the rewards that the market can offer more disciplined investors. The data also shows that when investors react, they generally make the wrong decision.” A mutual Fund is like a Unit Trust or KiwiSaver Fund in New Zealand.

I depart from the FutureSafe article and provide the graph below from PIMCO.

As PIMCO highlight, “Through no fault of their own – and especially when market volatility strikes – investors tend to be their own worst enemy.”

The graph below highlights that investors do not capture all of the returns from the market, which can be attributed to behavioural biases that leads to inappropriate timing of buying and selling.

This investor behavioural gap is well documented.

In reference to market timing and in one short sentence, FutureSafe say “We’re probably not as good at these active calls as we think we are, and it might hurt more than help.”

Reason 2

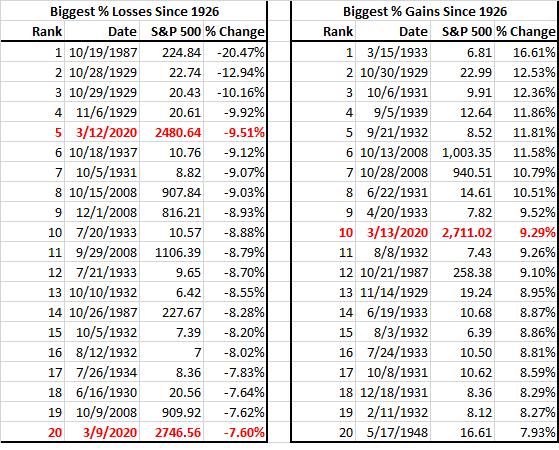

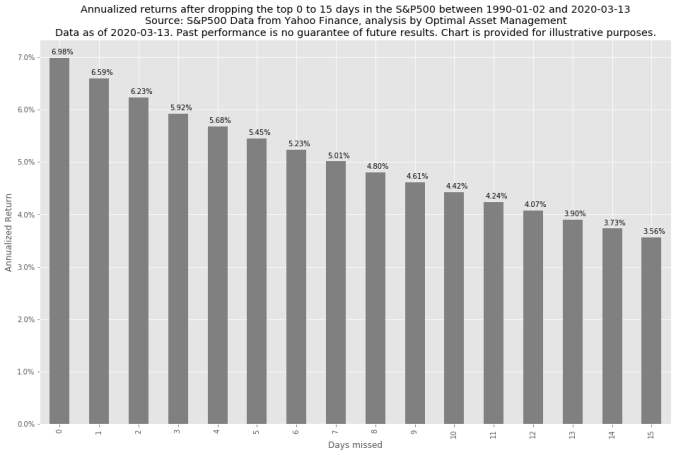

A large portion of returns are earned on days markets make large gains.

Although the extreme volatility being witnessed currently is very painful to watch, amongst them are explosive up days. Attempting to time markets might cause you to miss these valuable up days.

The research on this is also very clear.

As outlined in the Table below, if you had missed the top 15 biggest return days your yearly return would have been 3.6% compared to 7% per year if you had remained fully invested (this is over the period January 1990 to March 2020 and being invested in the US S&P 500 Index).

Of course, the same can be said if you missed the largest down days. Nevertheless, good luck at avoiding these days and still being able to fully capture the returns from equity markets. The down days represent the risk of investing in shares.

Most important is having a disciplined investment approach and an investment portfolio consistent with your risk appetite and is truly diversified so as to limit the impact of the poor periods of performance in sharemarkets.

In summary, FutureSafe note, “Missing just a few of the top up days, can cost you a large chunk of the market’s returns.”

Reason 3

Take a long-term perspective.

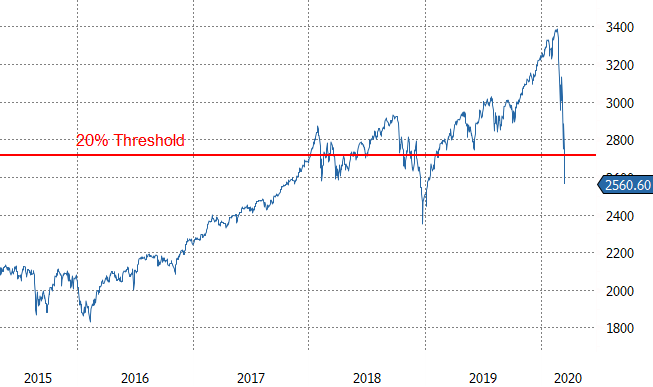

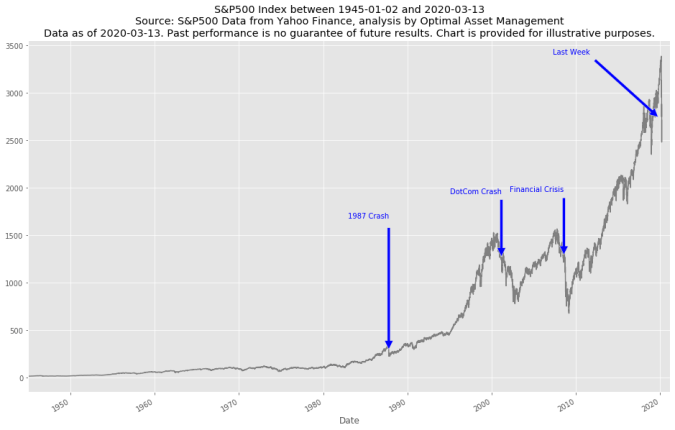

Overtime, and with hindsight, large market declines look like minor setbacks over the longer term, the very long term.

This is quite evident from the following graph.

Remember, the stock market fell by 20% over one day in 1987, the dot-com crash of 2000 or even the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 don’t look to bad with a longer term perspective.

As FutureSafe conclude “If you really don’t need the money for a long period of time (e.g. 10 or 15 years) these are best to ride out because they look a lot better in the rear view mirror than when you are going through it.”

“If you have a long enough horizon (10 to 15 years or more), the chances of doing well in the stock market is still quite good.”

Therefore, the key points to consider are:

- Risk Appetite should primarily drive your allocation to sharemarkets, not the current market environment;

- We can’t time markets, not even the professionals;

- Be disciplined and maintain a well-diversified investment portfolio, this is the best way to limit market declines, rather than trying to time markets;

- Take a longer-term view; and

- Seek out professional investment advice

Keep safe and healthy.

Happy investing.

Please read my Disclosure Statement